King James I & Charles I's Palace Yard

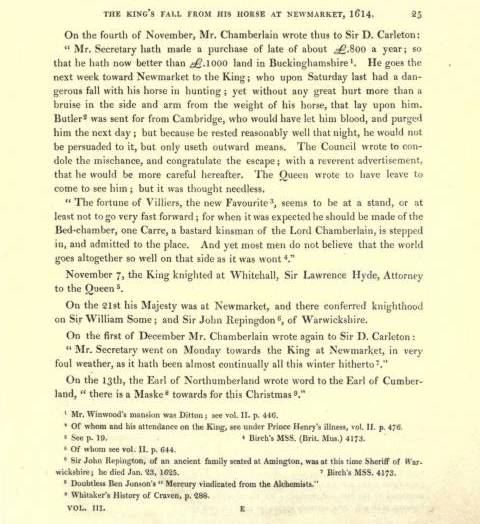

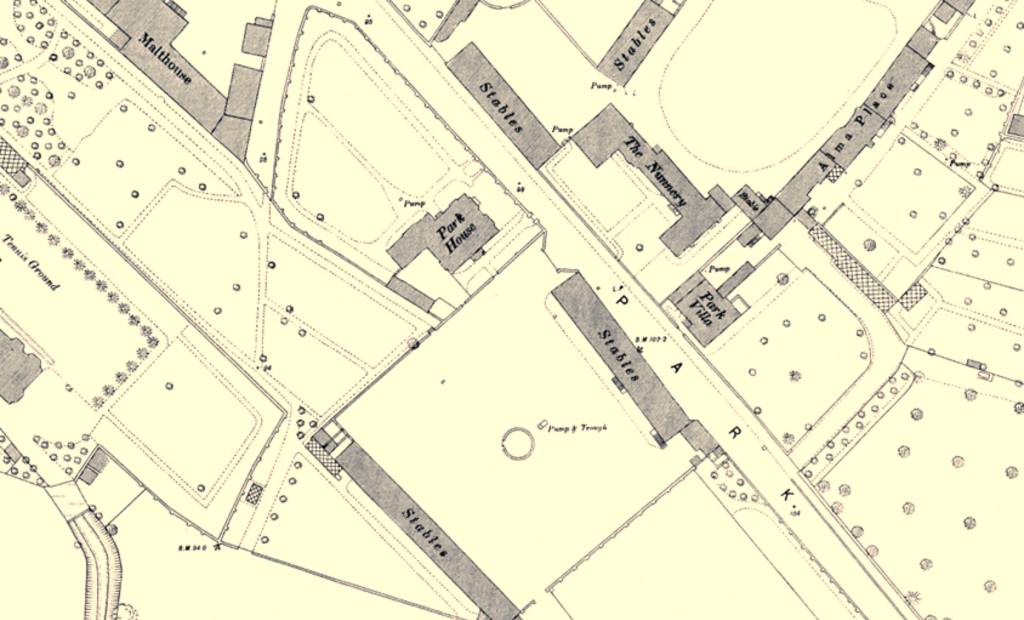

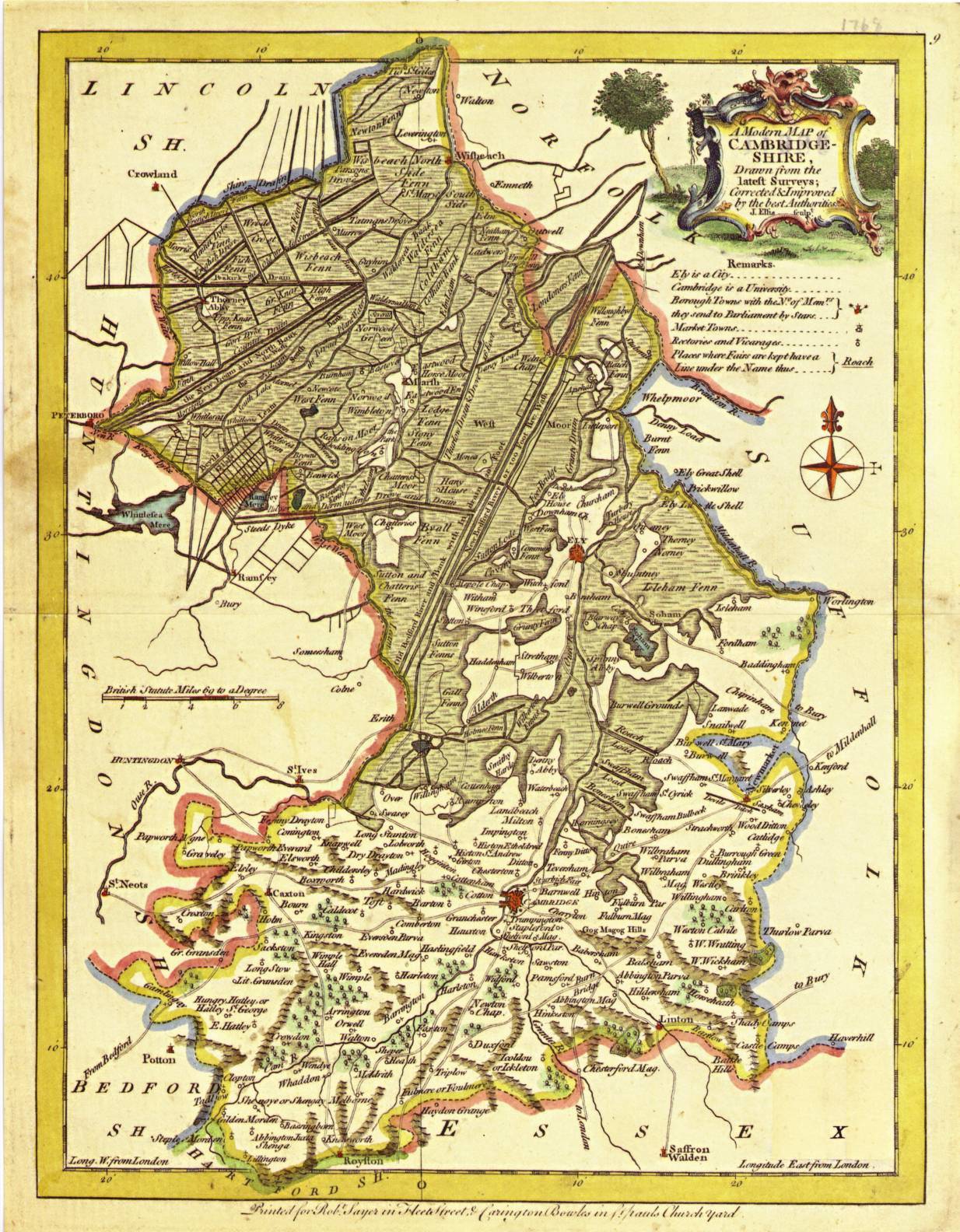

- Chapman's map of Newmarket below is 137 years later that the last

detailed record of when James I and Charles I's palace stood here, shortly after which most of

the main palace buildings were demolished, but the context of the

plot of land is still very much evident and relevant, and the area labelled

'Old Kings-yard' gives us a very big clue as to where this palace

actually was.

-

King James I & 'le Gryffyn'

-

Before we get into an in-depth explanation of who, what, why or where (royalty in Newmarket), let's just understand some basic family associations of this particular era (1603-1685) - what we have here is a grandfather, father and son - Newmarket's Stuart trilogy.

There were more Stuart monarchs than these three, but it was this trio that had the greatest impact on Newmarket.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/House_of_Stuart

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/House_of_Stuart

-

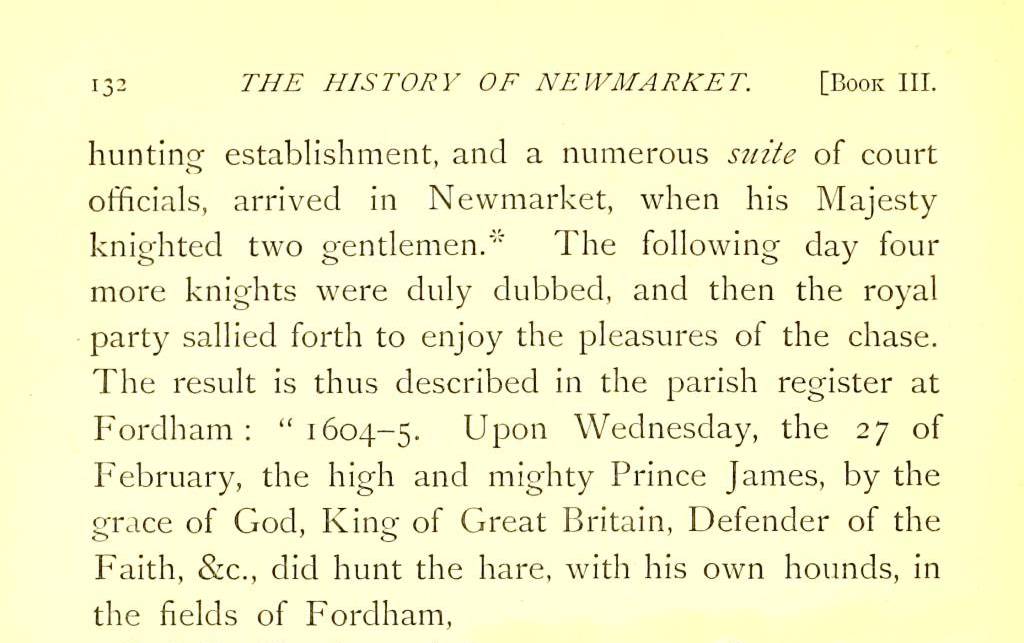

It was the grandfather, James Stuart - King James I of England and VI of Scotland (1566–1625), who began the love affair with Newmarket - he first visited the town from the 26th to 27th February 1605 on his way to Thetford - '... royal party sallied forth to enjoy the pleasures of the chase ... to hunt the hare'. The King identified the heath as an excellent place for hare coursing with greyhounds and hawking and having taken a liking to Newmarket he used to stay at the Griffin Inn in the town.

Extract from ‘The History of Newmarket & the Annals of the Turf - J.P. Hore 1886’

King James I c.1606

King James I hawking

-

As shown in further details below from J.P. Hore's book about Newmaket, on 11th February 1608 James purchased the remainder of the lease of the Inn from a Richard Hamerton, who subsequently on 20th April 1608 was appointed keeper of "the king's house at Newmarket".

Going back 136 years before the king arrived, these were the buildings present in Newmarket in 1472 - starting from Sun Lane (originally Guildhall Street) and moving westward:-

In the subsequent year James also purchased further land in Newmarket ... more details about that are shown below.

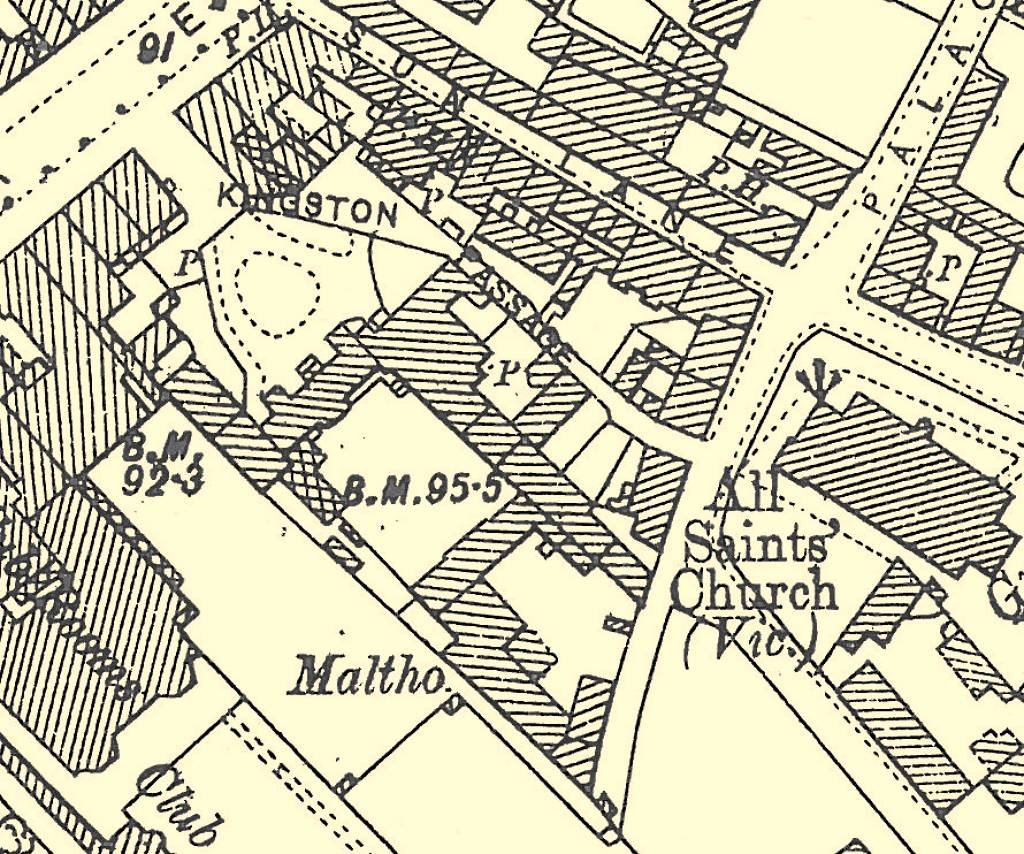

Chapman's Map of Newmarket 1787 (note that this map shows the old All Saint's church which was oriented east-west, before it was replaced by the present building in 1876-77.) |

| Description in 1472 | Present Address | Notable recent use | ||

| Richard Deresley | No.77 High Street | The Black Horse | ||

| The

Swan: John

Kyrkeby, John Thykenesse, Roger Holyngworth |

No.79-83 High Street | Cash Machine

/ Street Café / Best-one |

The Griffin: William Baron, Arthur Greysson | No.85 High Street | Moons Toymaster / Kings |

| The Bull: Margaret Landwade, John Motte, Margaret Motte, Richard Motte, Arthur Greysson | No.89-95 High Street | York Buildings | John Chaunderlere, Ralph Lote | No.97 High Street | Page Fine Jewellery |

| The Saracen's Head: John Koo, William Farwell, William Thoryngton, Roger Mayner, Arthur Greysson | No.99 High Street | National Horseracing Museum | ||

| The vicar of Wickambrook, Thomas Depden | No.101 High Street | The Jockey Club | ||

| John Ickelyngham, John Wykes | ||||

| Dundich | The Watercourse |

Names in italics are tenants. (Note that at its position

today the Watercourse actually runs under the ground of

the Jockey Club.)

- Many thanks to the Newmarket Local History Society

and the Reverend Peter May for the information of the landlords in

the town at that time (copies of his book 'Newmarket Mediaeval & Tudor'

can be purchased in bookshops and online).

[The details of the present addresses is purely surmise based upon the approximate known location of these occupants, various historic maps and the 1650 survey of the later palace grounds detailed below.]

Also as detailed in Peter May's book, when Arthur Greysson died in 1479 he'd previously acquired the Bull from Richard Motte and in his will he requested that 'the said holding called le Boole with its appurtenances be annexed and joined to the aforesaid holding called le Gryffyn'. This explains why the Griffin became such a large plot of land on the High Street.

[In case you were wondering with all 'le' this and 'le' that, up until the late 15th century the English language was highly Gallicised (French-based), particularly in formal documents such as this - 'le' being the French for 'the'.]

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_English_Language

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_English_Language

It's known that records of the Griffin go all the way back to 1439 (when William Baron left the Griffin as well as other land to his wife in his will), so it was already an ancient building when James I purchased it.

From 1609 to 1613 work was done to extend and improve the Inn; £457 6s 4½d in 1609, £59 4s 4d in 1610, £162 2s 8d in 1611, £85 8d in 1612 and £49 9s 11d in 1613, but in that year the rear section of the building collapsed with the King and his court inside.

Not deterred by his close brush with death James decided to keep his foothold in Newmarket and from 1st May 1614 until 30th September 1615 the much increased expenditure of £4,660 11s 9½d was paid to re-build the palace, this time in brick & stone.

Work continued in subsequent years and on 3rd October 1622 he purchased the Swan Inn next door to further extended the size of his palace here in Newmarket.

Extracts from ‘The History of Newmarket & the Annals of the Turf - J.P. Hore 1886’

Book III

Under date February 11, 1608, a warrant was granted to R. Hamerton for £500, for the remainder of his lease of the Griffin at Newmarket; and on the day following he received another warrant for £60, "for the king's charges at Newmarket."

Half-yearly payments of the rent for the Griffin continued to be paid until the fee simple was purchased in 1610.

Book VIII

The fame of Newmarket began soon after the destruction of the Spanish Armada. Some horses, which had escaped from the wrecked vessels, are said to have been exhibited here, and to have astonished those who beheld their extraordinary swiftness. In a very short space of time, racing had grown fashionable, and James I and his court became so enamoured of the sport, that a house was erected at Newmarket for their accommodation.

Book II

In the year 1589 a suit was instituted in the High Court of Chancery by Henry Greene, Robert Greene, Thomas Greene, and Haggas Greene, sons of Richard Greene, deceased, against Theodor Goodwyn, to redeem the Swan Inn, situated in the Cambridgeshire part of the town, and ten acres of land "in the fields of Ditton" which had been mortgaged by Richard Greene, father of the plaintiffs, to Thomas Frankes, for the delivery of a certain quantity of malt, from which we may deduce that malting was a somewhat important industry in Newmarket in those days as it was in later times.

Book V

The following extracts from the accounts of the Lord Treasurer's Remembrancer, preserved in the Public Record Office, show the cost of materials used in works and building, with the money disbursed for workmen, at Newmarket Palace, from 1609 to 1625.

Book V

The amount of money expended on the royal palace at Newmarket in the following year was no less than £4660 11s 9½d. This heavy expenditure was chiefly incurred for building with stone and brick a pile of new lodgings for the king, with a great chamber, presence-chamber, etc., and rooms both under and over the same for noblemen and gentlemen of the bed-chamber, as also for other works done there during seventeen calendar months, commencing May 1, 1614, and ending September 30, 1615.

Book V

On October 3, 1622, a warrant was issued to pay Sir Robert Vernon £150 for lands and inheritance belonging to the Swan, at Newmarket, taken for building offices for the king's use. - Docquet Book, s.d., MS., P.R.O.

The Sir Robert Vernon mentioned above had been the keeper of the 'Newmarket Palace' and garden since 1616, so this very much confirms that the Keeper's Lodgings itemised as facing the High Street in the 1650 survey below and the Swan Inn were indeed the same building.

At a time when roads across the country were few & far between and those that did exist were rough and unkempt, records show that King James frequently made the journey from London north along Ermine Street to Royston and then picked up the Icknield Way through to Newmarket and then on to Thetford, and at these stopping points he would partake in his favourite sports of hunting, hawking and hare coursing.

J.P. Hore's book details how James allocated money to improve the quality of the above roads, by filling-in ruts and building bridges to improve his journey through Royston and Newmarket into Norfolk.

King's House, Thetford

King James' Palace, Royston

James built 'palaces' at each of these locations - King's House in Thetford is a later reconstruction, built in 1763 on the site of the former palace, and part of the palace at Royston still exists in the town on Kneesworth Street, though once again this has been somewhat re-modelled over later years.

His palace at Newmarket seems to have been grander than either of these though - as J.P. Hore's book details that when built in 1614 it was of brick & stone and three storeys high, with the walls of the ground floor three bricks deep and the upper storeys two bricks deep. He also spent a lot more time at Newmarket; holding his court here, entertaining important heads of European countries, and he also knighted many of his own gentry in the town.

-

[Note from webmaster - one of the most ancient members of my

extended family; Sir John Repington was knighted by King James I

at Newmarket on 21st November 1614 (9 years after the Gunpowder

Plot) - see details below.]

-

King Charles I

- So this is where we come to the next generation, the father in the

middle of this Stuart trilogy.

After James I died in 1625 the royal association continued when

his son Charles took over patronage of the palace in Newmarket.

There are no overall pictures or plans of the King's palace, but there are a set of drawings produced by the architect Inigo Jones in 1619 of the proposed Prince's Lodgings. Shortly after this in 1627-1628 a bill of work for the palace refers to 'tileing over the dormer windows and other parts over the Prince's new buildings, etc.', so it's clear that this new building had been built by then. [This building must have been intended for the then Prince Charles as his older brother Prince Henry had died at the age of 18 in 1612.]

James I died on 27th March 1625 and almost a year later Charles I was coronated on the 2nd February 1626. He went on to become the king who nearly brought the whole British royal dynasty to an end.

One of his confrontations that initiated the English Civil War took place in Newmarket in 1642, when he met a parliamentary deputation and after being pressed by the Earl of Pembroke that he surrender the militia for a time Charles suddenly swore:-

"By God! not for an hour! You have asked that of me in this, was never asked of a King, and with which I will not trust my wife and children."

Newmarket remained Royalist throughout the war, but in June 1647 Charles was captured at Holdenby House in Northamptonshire and brought to Newmarket as a prisoner. He was placed under house arrest in his palace while the whole of Cromwell's New Model Army kept guard over the town.

After his execution on 30th January 1649 the palace was sold a year later and at that time a full and complete survey was performed (a bit like an estate agent's sales brochure) - from this we can glean quite a lot of information about the palace and its lands ... this is what we know:-

-

Survey of New-markett-house in March 1650

- 'Parcell of the possessions of Charles Stewart, late King of England. All that Capitall Messauge, Mansion-house, or Court house, commonly called or knowne by the name of

New-markett-house'.

- The Palace Yard

-

There were two buildings on the northern side of the main

palace yard facing directly onto the High Street, these

being the above mentioned brick-built Prince's Lodgings, which was

70ft (21.3m) long and the timber-built Keeper's Lodgings, which was

44ft (13.4m) long.

When Chapman's maps of Newmarket map were produced the majority of the palace buildings had long gone, but as is the case with many historic plots of land, unless they are drastically altered by major re-development the boundaries still remain, and in this instance give a very large clue as to the position and extent of the palace yard. From this it becomes obvious that the width of the Prince's Lodgings pretty much matches exactly the position of the present day York Buildings - No.89-95 High Street.

Interestingly King Charles I, as one of his titles, was the 4th Duke of York - so maybe when this building was built in 1832 they knew about the location of the Prince's Lodgings and named the new building in honour of him - if anyone knows any more about this please E-MAIL me.

In 1631-1632 the front of the palace fronting onto the High Street was fenced with post and rails. If you refer to the page for King Charles II's Palace much the same was done there. These palaces, although not particularly grand buildings, were still very impressive in their context of Newmarket High Street.

-

The Lodgings for the

Keeper of the 'house and garden' sat on the High Street

along with the

Prince's Lodgings.

Many more of the buildings in the main palace yard are listed in this survey, but their exact location is a bit more vague.

-

The timber-built Pantry,

Buttery & Wardrobe, connecting from the Keeper's

Lodgings to the King's Lodgings.

-

The brick-built King's

Lodgings, with its adjacent tennis court.

-

The walled garden on the

southside of the King's Lodgings - described as

approximately one Rood in area (1012sq.m). This is what is understood

to still exist behind the present Kingston

House, and is

being used by the next-door Kings Restaurant as an outdoor

seating area.

-

The part brick, part timber

King's Kitchen.

-

The timber-built Long Gallery

connecting from the King's Lodgings to the Prince's

Lodgings. This building also contained a range of lodging

rooms and offices.

-

On the west side of the Long

Gallery, separated from it by a wall, was a similar building

containing a range of lodging rooms.

What we have here is a building that was behind the Prince's Lodgings on the west side of the king's yard ... hence this is the present-day location of the buildings associated with Malton House - No.87 High Street (at one time the home of the race-horse trainer Alfred Hayhoe).

Previous research into the history of Malton House has shown that part of it may have been contemporary with the king's palace and hence the origins of it could be these lodging rooms detailed in the 1650 survey.

-

A turreted brick-built

Prince's Kitchen.

-

The remainder of the site

contained various other timber buildings and the whole site was about one

acre in area and surrounded by a stone wall on the west,

south and east.

It's known from this survey that the rear of this site abutted onto All Saint's church yard and as shown on Chapman's 1787 map there was a road that ran directly from the church to Woodditton from here, hence the reasonable assumption is that this road demarked the southern boundary of the palace site.

Piecing together all these details we come to the boundary outline in red on the map at the top of this page and also highlighted in BLUE on the smaller scale map below.

-

The survey doesn't stop here

though and it goes on to detail many other buildings and

plots of land that were still owned by the monarch.

- The Stables, barns, riding house and kennels

-

The list of other buildings in the

survey are too extensive for this web page, but one

interesting location is the 'Dogghouse' - the kennels - and

although they may not be the exact same buildings, the

kennels are still shown on Chapman's 1787 map below - the

present-day location of these being approximately at the corner of Park

Lane and Green Road and indeed the original name of Park

Lane was Dog Kennel Lane.

Built in 1615-1616, the original 'Dogghouse' was much more than just dog kennels though - it was brick built, 44ft by 28ft in size, and was two storeys high, with lodging rooms for the master of the hounds on the upper floor. There was an adjoining brick-built stable and a garden that was one Rood in area (¼ acre - the same size as the King's garden). The whole site was surrounded by a 'Pale & Stonewall'.

J.P.Hore's book details that it was beagles being kept here; the King's privy hounds, to be used in his much beloved hunting and hare coursing.

- The Six Acre Paddock, King's Closes & Hare Park

-

The 1650 survey gets a bit vague

here, but it refers to a 6 acre plot of land south of the

church, which matches that shown in GREEN

on the

map below

and also 11 acres of land 'in severall Places & Parts'

separated from the other lands 'divided from ... by

the Common Street or highway with the Church and Churchyard'

- the King's Closes.

Unfortunately it's not clear in the survey exactly which particular pieces of land are included in the King's Closes, but the inference is that it refers to all the land in Newmarket that wasn't directly part of the enclosed palace yard, and it would also seem to include the whole of the unmarked paddocks south of the 'Cock-Pit' in the top right corner of the map below (note that until it's been proven that this was indeed the case it's presently not been coloured or outlined on the map). If this particular plot of land was indeed originally owned by the monarch it's then becomes clear how Charles II was subsequently able to build his stables and also Nell Gwynne’s House on land that was already his.

The survey also details several pieces of land 'upon the common heath ... severrall parishes of Swafham Bulbecke, & Burrow Greene ... commonly called ... Hare Parke'. Hare Park is just Newmarket side of Six Mile Bottom and James initially owned this land as it enabled him to continue his passion for hare coursing - which is what attracted him to Newmarket in the first instance.

- The Greyhound Inn

-

Finally the survey details

several pieces of land containing buildings and brew-houses

that were behind the Greyhound Inn in Newmarket High Street, amounting to about 1-1/2 acres.

Further details about the Greyhound can be found on the page

for Charles II's Palace

and the later incarnation of the inn on the other side of the road at No.82

High Street, which eventually became the Carlton

Hotel.

-

The extended Crown lands

- As can be seen in the land map above

one other fact that becomes very obvious

from all the above details is that the king owned significant land

on the southern side of the Newmarket High Street.

-

1821 Enclosure

- The 1821 enclosure map for the

Woodditton parish / southern part of Newmarket show that the 4

acre plot of land highlighted in RED

on the

map above was by then owned by

Edward Weatherby, the well known Secretary and Handicapper to

the Jockey Club.

Most of the 6 acre plot of land south of the church shown in GREEN on the same map was still 'Crown Lands' with a small plot close to the church owned by F. Smallman (further details can be found out about this on the page for the 'Nunnery' stables). These 'Crown Lands' covered from All Saints car park, through Park Avenue, Queen Street, up to Granby Street and included the area later know as 'Paradise Row'.

The King's Closes was by then owned by the Duke of Rutland, as detailed on the page for the Rutland Arms Hotel - No.33 High Street.

-

Re-construction of the palace

- The 1650 survey

contains a lot of detail, not only itemising all the

important buildings of the palace, but also giving their plan dimensions and the

approximate inter-relationship between these buildings. But in

addition to this there are also a variety of other maps and plans

made at later dates that help with this re-construction:-

- Thomas Fort, Clerk of Works

(1719-1745), produced a survey map of the various plots of

land owned by the crown at that time, which shows what was

left of the old palace after demolition by the Interregnum.

- There's a detailed surveyor's

map made on 8th June 1756 of the old palace yard, which by

that time shows Kingston

House as having been constructed.

- Also Chapman's

maps of 1768 and 1787 shows what was on this site at those times.

- And finally in 1831 a very detailed surveyors plan of the

entire plot was created when the land was sold to the businessman

Stephen Piper, one of the progenitors involved in the building of

the Congregational Church

on the site of Charles II's Palace.

Hence although there are no actual plans of the palace itself, combining all these various details together the map below shows a possible arrangement of the main palace yard.

Below the map, the 3D digital re-construction images are even more interesting - a whole variety of facts and references have been used to construct these.

There's been one small detail that has made this re-construction slightly problematic - the 1650 survey only gives overall length and breadth of the buildings- it doesn't given any height of the buildings and also it doesn't take into account any irregularity of shape - i.e. side buildings, sheds, adjoined lean-to's etc. - so a great deal of artistic license has had to be used in building design, based upon what buildings were present in later years and a wealth of architectural cross-referencing to contemporary buildings of similar structure. With consideration being taken of building techniques and capabilities of the late medieval period.

Hopefully what's shown below is a reasonable facsimile of what was most likely to have been present in the old palace [Note from webmaster - If any anyone has any further information or finds that anything shown on this page is glaringly wrong, please do E-MAIL me.] - Thomas Fort, Clerk of Works

(1719-1745), produced a survey map of the various plots of

land owned by the crown at that time, which shows what was

left of the old palace after demolition by the Interregnum.

The extended palace lands as shown on Chapman's Map of Newmarket 1787 (see details of the 1650 survey above for the key to the various plots of land) |

The King's Lodgings

- Built in 1614-1615 we know from details in J.P. Hore's book and the 1650 survey that the King's Lodgings was three storey ('rooms both under and over the same for noblemen and gentlemen') and constructed in brick & stone - 'The walls of the new buildings were three bricks in thickness from the foundation to the ground-floor, and from that elevation upwards they were two bricks in thickness.' In order to better visualise what the building could have looked like it seems appropriate to look at other 'palatial' buildings that still exist elsewhere in the country that were built around this same time in history - we have two prime examples:-

Firstly we have Ham House in Richmond, Surrey - the National Trust credit this house as being 'unique in Europe as the most complete survival of 17th century fashion and power'. It was built in 1610 (four years before the Newmarket palace) by Sir Thomas Vavasour, Knight Marshal to King James I, so it's context is extremely relevant as a possible comparison for the King's own lodgings.

Ham House

Secondly we have Highnam Court, Gloucestershire - this was built in 1658 after the original house was seriously damaged during the Civil War and is one of the few grand houses built during the Interregnum. It therefore dates about 44 years after the Newmarket Palace, but the relevance here is that its design is credited to Ernest Carter, who was a pupil of Inigo Jones (designer of the Prince's Lodgings detailed below). As expected it's clearly more 'Italian Renaissance' in style than Ham House, but the architectural similarities between the two are obvious, if not only for the materials used (brick & stone).

Highnam Court

Being three storeys high Ham House is probably the closest to what we expect the King's Lodgings to have looked like and it's more contemporary with it than Highnam Court, so the re-construction will follow its architecture more closely ... with just a few aspects from Highnam Court; such as the roof dormers, which other Newmarket buildings also seem to favour (including the Princes Lodgings below and even the present Kingston House on this site).

There's one small aspect of the re-construction of the King's Lodgings that's pure artistic license - considering that Ham House is most probably the closest surviving example we have of what Newmarket's palace looked like, the rear door exit from the house into the garden has been based entirely on that visible in the photo above. There's no contemporary details that state that this area was actually like this, but the King would have needed an easy means to alight into his garden and some palatial steps like these could easily have existed here.

J.P. Hore's book details that most of the stone used in constructing the King's Lodgings was brought from Northampton - where they quarry both the pale red-cream sandstone and the slightly darker ironstone shown below:-

- Some further corroborating evidence has recently been found (21st Oct. 2014) that seems to support all the above suppositions about the shape of the King's Lodgings and this can be seen in the picture below, which is of Kensington Palace, London in 1724:-

Kensington Palace

The original building here began as a simple two storey Jacobean mansion built by Sir George Coppin in 1605 in the village of Kensington, this can be seen on the left in the picture ... so this house was built only 9 years before King James I's palace in Newmarket.

When William and Mary became joint monarchs in 1689, they bought the house and instructed Sir Christopher Wren to expand it to suit their requirements. In order to save time and money, Wren kept the bulk of the original building intact and added the three-story pavilions, which can be seen on the right in the picture.

If you compare the original contemporary building on the left to the re-construction views of Newmarket's palace shown below you'll see that they are indeed very similar - including the dormer windows for the servants quarters along the front roofline and with the almost identical Jacobean chimneys at the rear (a lucky choice for the re-construction).

We know from J.P Hore's book that Newmarket's palace was three storeys high, so it would have also looked similar to the 1689 built addition on the right in the picture - so it seems that the architecture that's been chosen for the re-construction of the King's Lodgings has ended up being a hybrid of the two parts of Kensington Palace - very appropriate for its intermediate build date of 1614.

Not shown here, but there are some plans available showing the internal wall structures of Kensington Palace and these detail that the original house was a very shallow depth building, almost identical in size to the King's Lodgings here at Newmarket - so from these plans we get a good comparison as to how the rooms inside Newmarket's palace could have looked - most probably palatial, but not very spacious.

And finally, Kensington palace even has a Jacobean-style turreted clock tower (top-left), not dissimilar to the design used for the Prince's Kitchen detailed below - re-confirming that the architecture chosen for the re-construction is entirely applicable.

The Palace Garden & Well

- The garden is documented in the 1650 survey as being one Rood in area - ¼ acre, and located to the south of the King's Lodgings. As the 1660 re-survey states, it was one of the few survivors of the demolition (I suppose you can't really demolish a garden). As such its presence is shown on all the three survey maps and hence fortunately most of the original garden is still present today, with only the southern most area now covered by the conservatory of Kings Restaurant (as can be seen in the photo below).

There are two wells detailed in J.P. Hore's book that were within the palace yard, with quite a lot of references to them, so we know that there were definitely wells here at that time. The location of the two wells is given as one being near the stables and another for use by the King's and Prince's Kitchens. Now all three of these locations were quite distant from one another, and unfortunately neither of the wells is marked on the two earlier survey maps, so this leaves us with no obvious locations as to where they could have actually been.

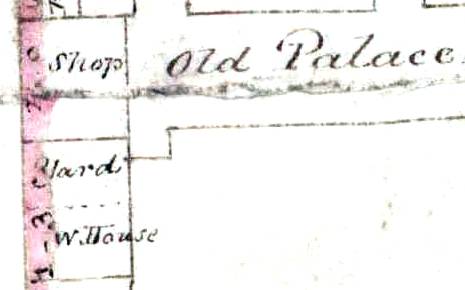

Today there's a well in the garden up against the very tall section of the garden wall (just to the right of the conifer in the photo above), and this is the particular location shown on the re-construction map below. As can be seen in the cropped section of the 1831 sales map shown below there's a small building labelled 'W.House' at this same position. The handwriting on the map is untidy and it looks like it could have been slightly altered ... the two uprights of the 'H' do very much look like they could have originally been linked to W. - i.e. the label could have started out being intended to be written as 'Well House'.

It's such a coincide that this building is at exactly the same location as the present-day well that this is its most likely interpretation, in which case we know that the well existed in 1831, but unfortunately no direct evidence that it could have been there at any earlier time.

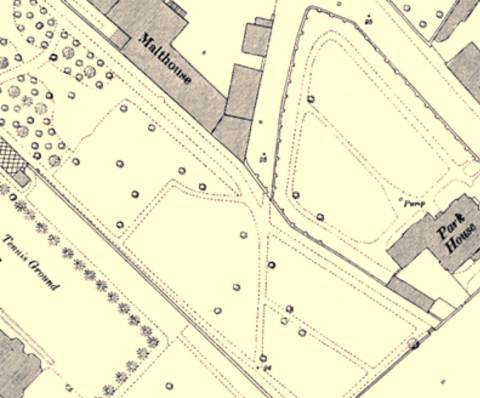

The Tennis Court - Real Tennis

- Kings James' father, King James V of Scotland, built the tennis court at Falkland in 1540/1 and brought 'real' or 'royal' tennis from France - so this is obviously where our James got his interest in the sport.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Real_tennis

From the 1650 survey we know that this was an impressively large building, but other than being brick-built there's nothing more in the survey about its outer construction. J.P. Hore's book does describe detailed building work inside on the court itself though, and from this we know that it was very similar to the Real Tennis court building that still exists today in Newmarket in Fitzroy Street, details of which are given on the page for Crisswell's Garage.

Extracts from ‘The History of Newmarket & the Annals of the Turf - J.P. Hore 1886’

Book VIII

The bill for 1627- 1628 amounts to £113 16s. 3½d. for black touch stones "for the hazard in the tennis court and new paveing and blacking the walls, peires and butresses of the same; "planking the king's stables; rematting and mending the mats in the privy lodgings; tileing over the dormer windows and other parts over the Prince's [Charles II.] new buildings, etc., etc. ; workmen's wages, carriage, etc., make up the total above mentioned.

Book VIII

In 1633-1634 the sum of £165 17s. 5d. was expended on the works and buildings of the royal establishment at Newmarket. The glass windows of the tennis court were protected with wirework, and 6d. was now spent on the purchase of wire to repair that work.

Book VIII (1650 survey)

And all that Brickbuilding commonly called the Tennis Court, & two other small Brickbuildings equall therewth & seytuate at the North & South Ends thereof conteyning together & in the whole by estima'con in length one hundred & twenty foote & in breadth Thirty & six foote, bee the same more or lesse.

Though there are no plans of James' Real Tennis court, the 1650 survey details a main court building with two small buildings at the front and back. This description is very close in layout to the court at Hyde in Bridport, Dorset as shown in the photo above (though this court has the small entrance building only at one end).

Though historic Real Tennis courts vary slightly in size, generally the internal size of the court at this time was approximately 90ft by 30ft, coupled with the double-ended entrance buildings this fits very nicely in the overall size of 120ft long by 36ft wide.

One particular difference between the Hyde court and this re-construction is with the area where the King's Lodgings butts up against the Tennis Court - there's a square shape of walls that's shown on Thomas Fort's survey of the empty yard after the remainder of the palace had been demolished, with a similar section of walls showing on both the later survey maps and is also still present in the buildings today at the junction between Moons Toymaster and Kings Restaurant.

If you have a look at the satellite image of the building today on Google Maps there's a real mismash of roof-lines in this area, showing that the historical sequence of construction of this area is really quite complicated.

With this square of walls in mind, and based upon some simple geometries derived from the 1650 palace survey, the front entrance room into the tennis court (which we know was still standing after the demolition) has been re-constructed as a building which is 5.5m wide by 4.2m deep.

The above photo is from a brochure for the building for the sale of the Marlborough Club. This brochure also includes quite a detailed floor plan and it shows that this room is the one right at the front of Kings adjacent to the front entrance, with the two full height ground floor windows looking onto the High Street.

According to the re-construction this room would be the location of the front entrance building to the Tennis Court. The comparative area within this room is actually 5.5m wide by 4.2m deep.

Clearly the re-construction is beginning to show some real substance about the interplay between the palace buildings , even though we'll probably never know for certain what was actually originally there.

IMPORTANT UPDATE December 2014

- A more detailed version of Thomas Fort's survey map has been found, dated between 1727 & 1745. In addition to the general building outlines shown on the original survey map this copy goes into much more detail and shows all the structures of the walls; windows, door openings, fire-places and even staircases. This allows a more comprehensive predicted building structure to be produced, with much less guessing and cross-referencing to other similar buildings being required.

The 'square of walls shape' detailed above is still very much evident on this plan, though now it can be seen that this is made-up of a rectangular building across the front and a similar rectangular area at the rear, which although surrounded by walls on three sides was actually just an open courtyard, with a post & railing fence on the eastern side (where the Tennis Court had originally been), the wall of the garden on the western side and the still remaining coach houses to the south.

This new form of the building does still confirm one very important aspect - scaling from other known details on the plan, it still predicts that the size of this room was 4.2m deep.

These additional details have now meant that the shape of the Tennis Court entrance is much more obvious and that it actually extended across into the length of the King's Lodgings. Interestingly the total width of this entrance building is now more like that as found today at the front of King's Newmarket Restaurant. It most probably means that as this brick structure survived the demolition of the palace that actually it still forms the core of the present building and that the room shown in the above photo is most probably the only surviving part of the original palace - quite a sobering thought.

The level of detail in the new map is also present in some of the other buildings - notably the Keeper's Lodgings & Pantry, the coach houses & forge and what became William Tregonwell Frampton's house. The shape of these buildings is not so much in conflict with the present re-construction as was the Tennis Court Entrance, but the plan does better show the location of the windows, doors and chimneys, hence progressively from now these will be added into the images ... watch-this-space.

The Keeper's Lodgings & the Pantry, Buttery & Wardrobe

- The Keeper's Lodgings was the building on the left-hand side of the palace yard facing onto the High Street. Quite a lot is known about the house and coupled with details about the later Lakeman's Bakery on this same site (as detailed in the King's Yard section below), the re-construction of this building is based upon 20th century photos of the bakery ... made to look like the original Swan Inn that it had evolved from.

The plan of the building in the re-construction though has been difficult to ascertain, as it's known that it was also joined to the 'Pantry, Buttery & Wardrobe'. This extension was quite a long building and is described in the 1650 survey as 'all that Crosse old Tymberbuilding' - so a simple timber-framed building of the documented size is shown here.

Although the outline dimensions of these two buildings are given in the 1650 survey their precise shape and arrangement is not. Also when you compare all the various survey maps detailed above the shape changed quite a lot between them. What is clear though is that there was a certain section against the High Street that remained the same, so the re-construction contains that particular section.

The 1660 re-survey does detail that the Pantry was one of the few buildings remaining after the demolition of the palace and interestingly in Thomas Fort's survey map (the earliest-after map) a very clear rear extension can be seen attached to the Keeper's Lodging that's not present in the later maps - the assumption here therefore is that this is what remained of the Pantry.

There's one additional detail that's not particularly important to the remainder of the palace, but it's impact on these buildings is key in understanding their particular shape and position. It's known that there's an ancient right-of-way that passes right across the palace yard from the High Street through to the church - this is what's shown on the map below as 'Common Churchway' (as it's called as on the June 1756 survey map). This pathway today is now Kingston Passage, also previously known as All Saints Passage. The significance of this pathway here is that whatever shape the 'Pantry, Buttery & Wardrobe' was, its position cannot have interrupted the route of the path.

- The extract show below is from the 'Codex Juris Ecclesiastici Anglicani' - more commonly known as the Statutes ... of the Church of England, and it details the public access rights applicable to a 'Churchway'. The understanding is that it's a private access way for the parishioners of the church, governed by church law.

It's interesting that in section III that there's an inhabitant who made a plea of prohibition in the 'Spiritual Court' in the 16th year of King James I - this is 1618/9 - it could very well have been that is was James himself over the public's right-of-access to this specific 'Churchway' in Newmarket (Kingston Passage). The extract goes on to state that 'Prohibition was granted' i.e. that the path was for the private use by the parishioners and that public access was by 'permission only'.

James was highly religious (James I's Bible translation 1604) and was probably the most important parishioner of what was still at that time called St Mary's Church, now All Saint's ( I know this means that there were two St Mary's churches in Newmarket, but that's how it was).

The shape of these buildings (the Keeper's Lodgings & the Pantry, Buttery & Wardrobe) shown in the re-construction hopefully satisfies all these disparate constraints.

[Note that a Buttery was not a room used for making butter! ... the Buttery was intended for storing and dispensing beverages, especially ale. In Medieval times water was not safe to drink so people mostly drank ale and wine. The origin and meaning of the word comes from the Middle French word 'botte' meaning cask. The person who presided over the buttery was called the Butler.]

- December 2014 Update - Details from the improved resolution copy of Thomas Fort's survey map have helped in adding a lot more detail to these particular buildings, albeit still leaving some unanswered questions. It's known that the Keeper's Lodgings and Pantry survived after the demolition, so it's to be expected that a large proportion of these would still be present on this survey map, and this does seem to be the case.

Firstly the plan shows the internal structure of these buildings, showing where the doors, windows and fireplaces were located; so these structures can now be modelled with much more accuracy. There's also one particular aspect of the walls of these buildings that seems very curious - the walls of the western-most part of the Keeper's Lodgings appear to be of a thickness that would match the expectation of a wooden structure that it's described as being in the 1650 survey, but the eastern side of the building has much thicker walls (around 24") and at the rear of the house the side wall extends into a boundary wall of the palace grounds, which is known to have been constructed in brick, and hence it's expected that this side of the building also contained some brickwork.

The updated re-construction of this building now shows this segregation of building materials. Interestingly this difference in construction may have persisted all the way through to this building when it became Lakeman's Bakery - the side of the bakery against Kingston Passage was timber-framed, but the eastern side was rendered (and by that time this section also had a bay window added to the front).

The extended shape of the Pantry, Buttery & Wardrobe is still very much a mystery; as it's clearly shown on the survey plan that what had remained extended back at right-angles from the Keeper's Lodgings. If this building continued in a straight line, it's 1650 survey specified 88' length would have fully blocked the Churchway described above. Hence for the re-construction although the first section of this building now matches the survey plan, the remainder has still been placed at angle to keep the passage clear. This aspect is complete guess work though and awaits any further evidence to prove or disprove it.

What can be seen in the survey plan of this rear building is described in the 1660 re-survey as having been the Pantry. What can be seen in the plan at this location is a very curious circular structure, with an opening on one side and is buttressed by thick pillars on the remaining 3 sides. Out of context this structure makes no sense, but if you refer to the page for Golding of Newmarket - No.67 High Street an archeological survey has been performed in the rear garden of this shop and this has identified an Ice-Well, believed to have been part of Charles II's Palace.

This archeological report describes the Ice-Well as follows:-

'brick lined, circular shaft, estimated to be 4.3m in diameter ... Constructed of red brick ... the shaft walls were 0.5m thick, leaving a central shaft 3.3m in diameter ... The interior of the dome was ribbed vaulted with brick groins.'

If a similar description was applied to the structure shown in the survey plan of the Pantry this would be as follows:-

'circular shaft, estimated to be 3.0m in diameter ... the shaft walls were 0.5m thick, leaving a central shaft 2.0m in diameter ... The exterior was ribbed with groins.'

The similarities are very obvious, but once again this is purely conjecture, though it would make every sense that the Pantry would have contained an Ice-Well.

The shape of this supposed Ice-Well has been modelled in the re-construction exactly as it appears on the survey plan and can be seen on the map of the palace shown below.

[In layman's terms an Ice-Well is an early form of refrigerator, sunk into the ground and filled with ice to keep its contents cool. Ice-Wells began to be introduced across Britain (the concept coming from France) in the early 17th century. It would make every sense that King James, with his very strong links to France, could very well have been involved in introducing an Ice-Well into his palace at Newmarket. Due to their construction there generally wasn’t any means of storing food in them and the ice was used in cooling drinks and for making cold confections in the kitchens.]

The Prince's Lodgings

- This was the building on the right-hand side facing the High Street. The re-construction has been based upon one of the possible designs that the architect Inigo Jones proposed for this building in 1619 - the option with the roof dormer windows has been chosen, as it's actually documented that these were built and used by the then Prince Charles to allow viewing over to the heath and his beloved racecourse.

There is a major proviso for the re-construction of this particular building though - although Inigo Jones was commissioned to produce a design for the house, there's no evidence in the accounts-of-works detailed in J.P. Hore's book that anything as near as grand as the Palladian architecture of his Queen's House at Greenwich (shown below) was ever built at Newmarket.

Queen's House, Greenwich

Construction of the Prince's Lodgings also cost much less than the King's Lodgings (£2719 compared to £4660), so although physically larger (44ft deep compared to 28ft deep) it must have been in some way more meagre than the King's palace.

Extract from ‘The History of Newmarket & the Annals of the Turf - J.P. Hore 1886’

Book V

The accounts for the following year are not extant, but in those for 1619-20, which amount to £2719 15s. 6¼d. we learn that some old buildings and sheds towards the street were pulled down and the ground cleared for the erection of additional lodgings of brick and stone, a wooden gallery, and offices for the prince. There were also a farrier's office and coach-houses built.

The Prince's Kitchen

- This was behind the Prince's Lodging House and is of the size specified in the 1650 survey. As detailed in the survey it has been given a turret of the shape that can be seen on many existing Jacobean buildings. The example below is from Blickling Hall in Norfolk, built in 1616, just three years before Newmarket's Prince's Lodgings.

The Long Gallery & Lodging Rooms

- The assumption has been made that the Lodging Rooms and King's Lodgings were actually originally one L-shaped building, and that these were the original Griffin Inn - this particular shape is highly likely, as there are many examples of old inns of this type of construction.

The rear section of the Inn fell down in 1613 and was re-built in brick & stone as the King's Lodgings in 1614.

The 1650 survey details that the only remaining part of the inn was the Lodging Rooms, located between the newly built King's Lodgings and the Prince's Lodgings. The building was of similar size and shape to the adjacent Long Gallery built for the Prince on the east, and the survey details that they had 'divers[e] lodging roomes or chambers both in the lowermost and uppermost storyes' - so three-storey timber-framed buildings have used for the re-construction of these.

The Courtyard, Wall and Front Railings

- There is no real detail in either the 1650 or 1660 surveys about a courtyard, but various walls and a set of 'great gates' do get a mention in J.P. Hore's book -

Extracts from ‘The History of Newmarket & the Annals of the Turf - J.P. Hore 1886’

Book V

... for bringing up the fence-wall by the tennis-court ... over against the great gates with brick and stone ...

Book VIII

... encompassed wth a Stone Wall on the West, South, & East parts thereof, & with the Common Street belonging to the said Towne of NewMarkett as aforesaid on the North.

From a security aspect though it's quite expected that the King's Lodgings would have been protected behind an encompassing wall, and based upon the previously mentioned comparative property Ham House (its gates are shown below) pedestrian and coach access through the wall would have also been via some impressive entrance gates - with this in mind the re-construction contains both a wall and gates.

Ham House

Behind this palace wall and gates we do of course create a courtyard ... and the later survey maps of Kingston House do indeed show a courtyard at that time ... though for the re-construction the shape used is more based more upon the wall that's still present at side of Kingston Passage today (as its dimensions are more accurately known). Interestingly the shape produced does fit very well with many of the other aspects of the original palace, particularly the requirement for the Common Churchway detailed above.

One other documented aspect of this wall has been included in its re-construction - as detailed above, it's referred to a 'fence-wall' - a very obscure description, so in an attempt to satisfy this reference its been reproduced as a (metal) fence on a wall.

- J.P. Hore's book also details that some post and rails were added in front of the palace along the High Street in 1631-32, so the re-construction shows these.

The King's Kitchen & Tregonwell Frampton

- The 1650 survey details this as 'standing distant from all other Buildinges'. So apart from knowing its outline size (40ft by 28ft) this makes placing this building slightly more difficult. But helpfully J.P. Hore's book gives us the following construction details in 1619-1620:-

Extract from ‘The History of Newmarket & the Annals of the Turf - J.P. Hore 1886’

Book V

For framing and raising "a roome on the back side of the kinges privy kitchen for the Marquis of Buckingham, with washing, boarding, lathing, and tileing the same, quartering a partition there;" and setting up racks, mangers, and stalls, and other miscellaneous work, including decorations to the ceiling of Buckingham's new lodgings, considerable expenses were incurred.

At this time the Marquis of Buckingham was George Villiers (1592-1628), and in June 1623, being both 'Master of the Horse' and 'Lord High Admiral of the Navy', he directed transportation of around thirty-five horses from Spain, which had been presented by the Spanish Court to the then Prince of Wales, later King Charles I. So therefore we know this new lodging house next to the kitchen was used by the 'Master of the Horse'.

The later June 1756 map of the old palace yard shows the location of a house that had been used by William Tregonwell Frampton (1641–1727) - 'Keeper of the King's Running Horses' (details about him are shown on the page for Charles II's palace). This location is now the old pantiled building that faces onto All Saint's church, shown in the photo below - No.4-6 Park Lane, part of which is presently Brown's Hairdressers (although this wasn't Frampton's house at the time of the palace, its known position is shown on the map below).

As the roles to the crown of both Buckingham and Frampton were very similar, it therefore seems highly likely that the house built for the Marquis was later used by Frampton.

As detailed in the December 2014 update above the shape of what had been the Master of the Horse's house is shown quite clearly on the larger scale version of Thomas Fort's map; this includes the position of the door, windows and fires places; hence these additional details have been included in the re-constructed outline of this building, which now also includes details of the fenced-off garden that's shown in front of it on the plan.

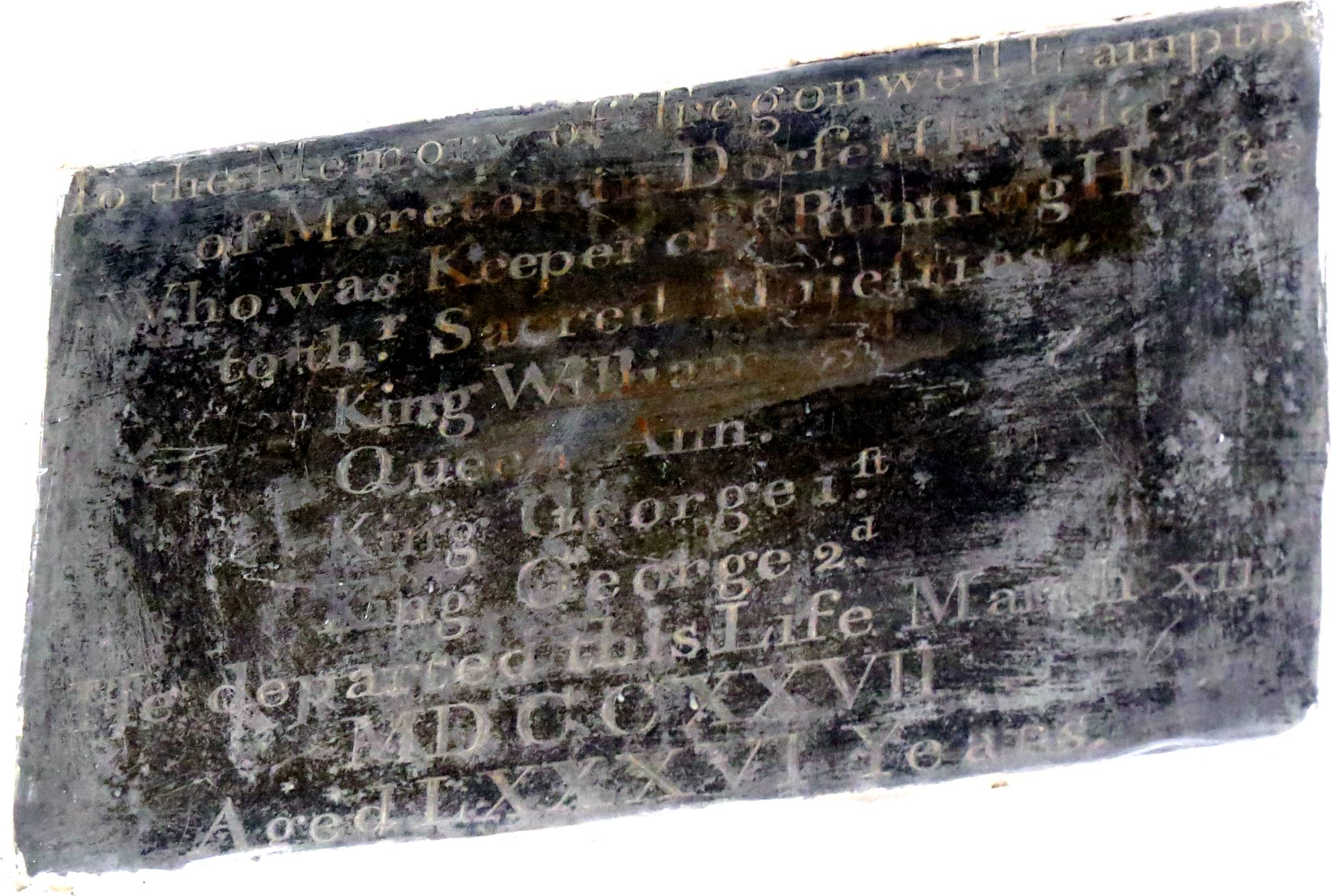

Just across the road from Frampton's house his memorial plaque no longer lies over his tomb, but is situated high up on the wall inside the vestibule - it's still clearly visible today and details of it are shown below:-

In the Memory of Tregonwell Frampton

of Moreton in Dor∫et∫hire, E∫q.

Who was Keeper of ye Running Hor∫es

to thr Sacred Maje∫ties

King William 3d,

Queen Ann,

King George i∫t

King George 2d.

He departed this Life March xii

MDCCXXVII

Aged LXXXVI Years

[Note the old document long s character, which looks very similar to an f is no longer available in a modern character set

- its use in the above transcript has been substitued by the integral character ∫ ; which looks very similar.]

Looking at the later surveyor's maps the building that was positioned next to Frampton's house was variously dimensioned at 36' 9" x 26'8" and 42'1" x 26'6" (shown on those maps as the 'Wood House' or just simply 'house'). These dimensions are almost an exact match (within a few feet) to those for the King's Kitchen given in the 1650 survey, and also this is the only building on those plans that was anywhere near this size. This re-construction therefore shows the kitchen at this location.

The present-day location of this building is Kingston Villa, the house that stands between Sun Lane and Kingston Passage ... but note that this, and any other building on this part of the site are all later constructions, as the original King's Kitchen was demolished by the Interregnum after 1650 as detailed in the 1660 re-survey below.

The view in the above photo of the present-day Kingston Villa from Sun Lane would have been the rear of the original King's Kitchen.

The Coach House & Forge

- The Coach House & Forge are particular buildings that do get numerous mentions in J.P. Hore's book - so from this we know that they were brick built, but unfortunately the 1650 survey is annoyingly vague about their actual location:-

Extract from ‘The History of Newmarket & the Annals of the Turf - J.P. Hore 1886’

Book VIII

And all that Brickbuilding or Ediffice commonly called or knowne by the name of the Coach house parcell thereof being vsed as a Smithes Forge now in the possession or occupa'con of one John Read or his Assignes ...

The 1660 re-survey though does detail that these buildings were still standing after the demolition of the palace and hence because of this fortunately they're position is still clearly evident on all the later survey maps.

From its title the larger of the buildings clearly had originally been a Coach House, but even by 1650 this was no longer its function and if you refer to the re-construction map below it becomes quite clear why - the plan shows that the coach entrances were on the eastern side of the building and following the building of the Tennis Court (1615-1616) these had been blocked.

After the demolition of the Tennis Court these entrances became accessible again and Thomas Fort's survey map (1719-1745) clearly shows multiple entrances along the eastern wall of these buildings.

The 1650 survey states that the workshop was 56ft long, and based upon meticulous scaled measurements from the survey maps it's clear that this only accounts for seven of the coach bays (it would seem that each of these bays was 8ft x 20ft - it's size obviously being dictated by its function as a coach house). The Forge is shown as a 20ft square building on the southern side of the workshop, but on the northern side there was an unused 3-bay coach house - i.e. an additional 24ft of building. The June 1756 survey map details that these 3-bays were 'excepted' from the payments detailed.

This re-construction contains all aspects of these investigations, which interestingly produces a set of buildings that fits nicely into the outline of the present-day buildings on this part of the site - the Kitchen of King's restaurant and also Chudleigh House - the back section of the Foresters' Social Club.

Even more interesting at this location is that the front section of the Foresters' Club, Amatola House, is an almost exact fit for the rear entrance building to the Tennis Court - another example showing just how well the re-construction is fitting the location of the present-day buildings.

- Cambridgeshire County Record Office, Cambridge

Sale Particulars

Reference 1026/SP/222-303

Covering dates 1886-1952- 1-2 Kingston House in Kingston Passage, Amatola House and Chudleigh House with coach house, corn chandler's lock-up shop and 2 cottages in same and trade premises in Park Lane, Newmarket. 1026/SP/260 7 April 1902

This latter house was named after Elizabeth Chudleigh, the Duchess of Kingston - details about her can be found on the page for Kingston House.

The Stables and Smith's Houses

- The plan of these buildings shown in the map below is not directly based upon details from J.P. Hore's book, but is the outline of the buildings that are shown on the June 1756 survey and 1831 sales maps. As such these particular structures were probably more likely to be associated with the later built Kingston House.

Hore's book does detail though that there were stables (built at the same time as the new King's Lodging House in 1614-1615), and also many other smaller ancillary buildings within the main palace yard, so their inclusion on this map is not to be historically accurate, but to illustrate how busy the site of the King's palace was.

An important note to point here is that these are not the same stables as the Inigo Jones designed 'stables of the great horses' that the book details were later built in 1619 further along the High Street. Plus there were also quite a few additional stables in the other plots of crown land south of the palace.

The 1660 re-survey doesn't help much in describing these buildings either, as after demolition of the palace all that it mentions was left were 'some other outhouses, and a stable next the church'.

Between about 1790 and 1828 these stables were used by father and son racehorse trainers, Thomas & Robert Robson - further details about them can be found on the page for Kingston House.

Interestingly if you refer to either the 1885 or 1901 Ordnance Survey maps of Newmarket (shown below) you'll see that the southern most section of the stables had become a Malthouse, presumably this was part of the maltings business of Stephen Piper, who purchased the whole of the palace yard in 1831 - details about him are shown on the page for Kingston House.

Today that area is the car park of Goldings Garage.

The Timber-yard and Stable

- The Timber-yard and Stable is another area that only gets a cursory mention in J.P. Hore's Book, and once again unfortunately their actual location is not given. The clue that's been used to locate them as shown in the map below comes from the 1756 survey map, where following the previous sad loss of the once grand King's Kitchen that location had become a 'Wood house & Hen house' - so the Timber-yard has been located immediately adjacent to this building, in the area that's labelled as a 'yard' on the later 1831 sales map.

Maybe not entirely conclusive as to their presence here, but the inclusion of the Timber-yard is two-fold, not only does it contribute in the same manner as with the above stables in showing how busy the King's palace was, but actually the yard was the source of a significant historical event. In 1615-1616 'A sum of 5s. is charged for extinguishing a fire that broke out in the timber-yard, which at one time threatened to destroy the palace and appurtenances.' Following the Gunpowder Plot in 1605, King James must have really felt that the world was out to get him.

The existence of the stable in the Timber-yard comes from the following extract in J.P. Hore's Book (V) - 'new lathing and laying the walls of the stable in the timber-yard with lime and chopped hay,' - from this we also know the walls were lime-washed, but this doesn't necessarily mean that they were white though, as very often additives such as pig's blood were mixed-in with the lime to produce an off-white colouring - this is where we get the colour 'Suffolk Pink', so favoured for houses in this area.

Later, as documented in the 1619-1620 accounts 'The woodyard was enclosed with a stone wall' (J.P. Hore Book V) - presumably this was done to make the area safer and contain any inadvertent fire, should it happen again. This must have been a real risk here - with the closeness of all the surrounding buildings and the possibility of falling hot ash in the smoke from their chimneys - this is probably why that by 1756 (as detailed in that survey map) the wood was then stored inside a house, which also had the added benefit of keeping it dry.

- There are a couple of very curious facts that come out of all of

this digital re-construction - even though it's known that the

original palace pretty much didn't exist past 1660, Kingston House

is very much the same size, and in much the same place as the

original King's Lodgings - and York

Buildings is the spitting image of Inigo Jones' 1619 design for

the Prince's Lodgings

(shown on the Home

of Horseracing website), with the only major difference in

outline being that it doesn't contain the roof dormer windows that

are known to exist on the original ... did somebody in the past know

more about the palace than we do now?

- One other interesting anecdote here is ... just look at the size

of the tennis court! - bigger than the King's Lodgings ... it's

therefore obvious that having fun was very important to the king!

... but then that's what Newmarket has always been about - a place

to come to have fun!

-

The 1660 re-survey for King Charles II

- 9 years after the execution of

King Charles I the resulting Commonwealth was in trouble and following the death of Cromwell in 1658

a political crisis

resulted in the restoration of the monarchy and the late

King's son, Charles (II) was invited to return to Britain on

29th May 1660, his 30th birthday.

Though the monarchy had been restored the Interregnum had been very cruel to the palace at Newmarket, demolishing most of it, and by August 1660 an update to the above survey detailed what little remained of the many buildings:-

Extract from ‘The History of Newmarket & the Annals of the Turf - J.P. Hore 1886’

Book XI

In August, 1660, a petition was sent to the king by Robert Ford praying to be reinstated as keeper of the ruins and relics of the royal palace at Newmarket, asserting that he and his father had held that appointment in the time of Charles I.

"of blessed memory," but that he, the petitioner, had been dispossessed during the Interregnum by one Okey, and others, by whom most part of the buildings were pulled down ; and as these persons still retained possession of what remained, he prayed they might be evicted in his favour, "that there may be noe more demolishing thereof."

Ford annexed a schedule of the parts of the palace then remaining, which only consisted of two brew-houses, the butteries, the old building next the street, a building at the end where the tennis-court was, the coach-houses, the forge, the pantry, some other outhouses, and a stable next the church.

Let us briefly see the extent of the dilapidations wreaked on this royal palace during those brief ten years.

Its heart of heart, known as the king's lodgings, a large brickwork structure, was razed to the ground ; the tennis-court adjoining disappeared ; of the kitchen no hearth remained ; not a stick of the long gallery was to be seen ; the erst prince's state lodgings now "were on the cold ground" with a vengeance ; no vestige remained of the numerous suites of offices thereunto belonging, neither upstairs nor downstairs nor in my lady's chamber ; the pantry survived as if to mark the site of the buttery, the wardrobe and the prince's kitchen ; the stables of the great horses, with the barns, the riding-house, and the kennels, were but memories of the past.

Not being destructible, the paddocks and the closes were still to the fore ; while, as if to show the irony of fate, the coach-houses and the forge remained extant.

All the minor and subsidiary appurtenances appertaining to the prominent features of the palace were as invisible as if they never existed.

The garden "was not much altered."

-

Fortunately after Charles I's death the royal connection with the town didn't stop there

- Charles II enjoyed horse-racing even more than his father; he was a jockey, as well

as a horse owner and trainer - hence the royal interest in Newmarket

was re-kindled, resulting in the construction

of his new palace further along the High

Street, labelled 'Royal Palace' in Chapman's map

above.

-

The King's Yard - what stands here today

- Although J.P. Hore's book

is only a later

transcription (1886), details in it were taken directly from

original documents, giving a very graphic, almost month-by-month

account of the acquisition and construction of James I's palace

(1609 onwards).

Going through these records in detail it becomes evident that the transformation from the original buildings to those that stand here today has only been progressive - there hasn't been a radical re-development. At one time this area was known as the King's Yard, and the details below show what conclusions can be derived about it from the various records:-

-

The Swan Inn

- On the left-hand side of the King's Yard we have the Swan

Inn, which was purchased by James I in 1622. This became the

Keeper's Lodgings. This was a timber building and was

still standing in the 1660 Survey

detailed above. There was still a house here as shown on the

1831 map on the page for Kingston

House. The side of the house against Kingston Passage

became a bakery in the mid 19th century, which later became

Lakeman's Bakery in 1924. This building was demolished in the

1970s and three new shop were built here - the present day No.79-83 High

Street.

-

The Griffin Inn

- In the centre of the yard, set-back from the road, we have

the Griffin Inn. It was originally constructed in timber, and

had been the King's first lodging house. Following its

collapse in 1813 it was re-built in brick & stone, and became

the main King's Lodgings detailed

above. After that building was demolished in the 1650s it was re-built by the Duke of Kingston-upon-Hull sometime after 1750.

This same building is now Kings Restaurant and Moons Toymaster - No.85 High Street.

-

The Bull

- On the right-hand side of the King's Yard we have the Bull, which had been annexed to the Griffin

Inn in 1479. Once again

this was originally constructed in timber and was re-built in

stone in 1619 to become the Prince's

Lodgings. After that building's demolition in the 1650s it was later re-built as two

houses and then in 1832 these were demolished and the present York

Buildings - No.89-95 High Street was built.

Each of the successive buildings on the above plots was built in almost exactly the same location as that before it - so what we have today is a fairly good facsimile of what the original palace looked like ... and even the three Inns that originally stood here.

-

-

Bricks in Park Lane

King James I & Charles I's Palace - 1650 - showing the original inns that had been in the High Street in 1472 [click on the picture for a larger view] |

|

|

King James I & Charles I's Palace in 1650 - Digital Re-construction - view looking south-west from the High Street © 2015 DaTeC-Design & Promotions Ltd. [click on the picture for a larger view] |

King James I & Charles I's Palace in 1650 - Digital Re-construction - bird's eye view looking south-east from the High Street © 2015 DaTeC-Design & Promotions Ltd. [click on the picture for a larger view] |

King James I & Charles I's Palace in 1650 - Digital Re-construction - bird's eye view looking north-east towards the High Street © 2015 DaTeC-Design & Promotions Ltd. [click on the picture for a larger view] |

York Buildings - location of the Prince's Lodgings |

|

|

|

| Location of the King's

Lodgings - Kingston House in the centre - Moons Toymaster, Kings Restaurant on the left and Malton House, the cream building on the right (click on the photos for a larger view) |

||

| Extract from ‘All the King's

Horses’ - A Celebration of Royal Horses from 1066 to the present day

- Amanda Murray Publication Date: April 1, 2006 There was change all round in that same year, Sir Christopher Wren, on visiting Newmarket, described the old palace there as a ‘vacant yard’. But it was a while before anything constructive was done, possibly because Wren and other top architects were devoting their time and energy to building projects in London in the wake of the great fire of 1666. The following year, Charles bought an old house off Lord Thomond that overlooked Newmarket High Street for £2,000 (£231,236 today), and he also bought the Greyhound Inn next door for £170.10s (£19,713 today) from a family named Piches. He then employed William Samuel, ‘a gentleman architect’, to construct a residence in which he could live and entertain. For now, his base continued to be Audley End, and in 1669 - despite the fact that construction work had begun in Newmarket - he offered to buy the house for £50,000, although the cost was never paid in full. |

Park Lodge Stables, Park Lane - 2014 |

- The photo above shows the corner of a wall of the Park Lodge

Stables in Park Lane - these are the stables opposite the Nunnery

(Sunnyside),

as shown in the 1885 map below.

Sandra Easom of the Newmarket Local History Society has commented that the bricks in the centre of this photo are older than the known age of the building. Their thin height is indicative of a much older brick than those that can be seen on the right in the photo, which are the very common 'Burwell White/Yellow' brick found in many places elsewhere in Newmarket (that must have been made at the local Burwell brickworks which opened c.1880 and closed in 1971).

The 1650 survey states that the Prince's Lodgings was brick-built and referring to the Inigo Jones proposal drawings for the building, it also had stone block corners.

In 1568 a royal charter defined the 'statute brick' as being 9" x 4½" x 2¼". After 1660 this increased to 9" x 4½" x 2½" and then after the brick tax in 1784 this increased to 9" x 4½" x 3" upto 3½" deep. Modern bricks are 8 5⁄8" × 4 1⁄8" × 2 5⁄8". Measurement of the bricks in the photo has shown that some are as thin as only 2" (50mm). As early bricks were hand made their individual size does vary greatly, but it's clear that these bricks must be classified as 'statute bricks' and hence are older than 1660 - clearly at this age they could easily be contemporary with the Prince's Lodgings.

The suspicion is therefore that these bricks were actually part of the Prince's Lodgings or surrounding buildings and that following demolition of the palace some of these bricks were re-used in the construction of these stables.

A curious fact here is that the bricks on the left in the photo are mostly the same buff grey as the much younger 'Burwell White' bricks on the right. Normally 'statute bricks' tended to be a bright red colour, as with those in Kingston House. What we possibly have here is a very early version of the 'Burwell White', made from a similar local gault clay that imparts this pale colour ... makes you wonder where they were made(?)

[The Brick Development Association's 'Guide to Successful Brickwork' - Gault a clay associated with chalk deposits in East Anglia. Generally bricks made with gault clay are cream or yellow in colour, but they may be light red - this description seems to fit those bricks above perfectly.]

As detailed above it's also known

that the Kings's Lodgings was brick-built (which is now Kings

Restaurant and Moons Toymaster - No.85 High Street), but there's

another theory concerning the use of its bricks which is detailed on

the page for that building.

-

Newmarket's Royal Heritage

- Further details about Newmarket's long and involved royal

associations can be found on the following page from the Newmarket Local History Society -

Newmarket's Royal Heritage:-

http://www.newmarketlhs.org.uk/personalities10.htm

http://www.newmarketlhs.org.uk/personalities10.htm

-

Charles I and the Fens

- It's unfair to only consider Charles I being attributed as the king who

nearly destroyed our monarchy, as his contributions to this part of

the country were considerable and much more than just the time he spent at Newmarket.

Charles, in association with the Francis Russell, the 4th Earl of Bedford (1593–1641) and other financiers - the 'Company of Adventurers' - were instrumental in the work started in the 1630s to drain the Cambridgeshire Fens. (Their business conglomerate was later called the Bedford Level Corporation, with the Earl's son being the first governor.)

The map above by the Dutch cartographer Johan Blaeu shows that by 1648 various drains had been cut across the fens, which included the Old Bedford River and the New Bedford River or Hundred Foot Drain (both named in honour of the Earl, who unfortunately didn't live long enough to see his work finished), but most of the area around Ely (the South Level) was still very much impenetrable marsh land.

Dutch cartographer Johan Blaeu's map showing the fens as they were in 1648

[click on the picture above for a larger view ... or on Johan's name for a very large view of the map]

Oliver Cromwell, with his homeland being the Fens, took an active interest in the project but was initially against the idea, mostly because of Charles' involvement. However after the execution of Charles in 1649 Cromwell gave his full support and employed another Dutchman, the engineer Sir Cornelius Vermuyden, to recommence the work and the South Level was completed in March 1653.

All this drainage work was happening within the same time period as the existence of the Palace at Newmarket (which as Blaeu's map above shows was mostly in Cambridgeshire at that time).

- Many thanks to Sandra Easom, Joan Shaw and many others in the Newmarket Local History Society

for their input and help in understanding the history and context of

this palace in Newmarket.

IMPORTANT NOTE from the WEBMASTER

Content on this web site is attributed as appropriate to its original source or supply -

can I ask that any copying or subsequent citation should respect the

original author(s) and reference them or this web site as the source of this material

Thank you

© 2016

- Return to top of page